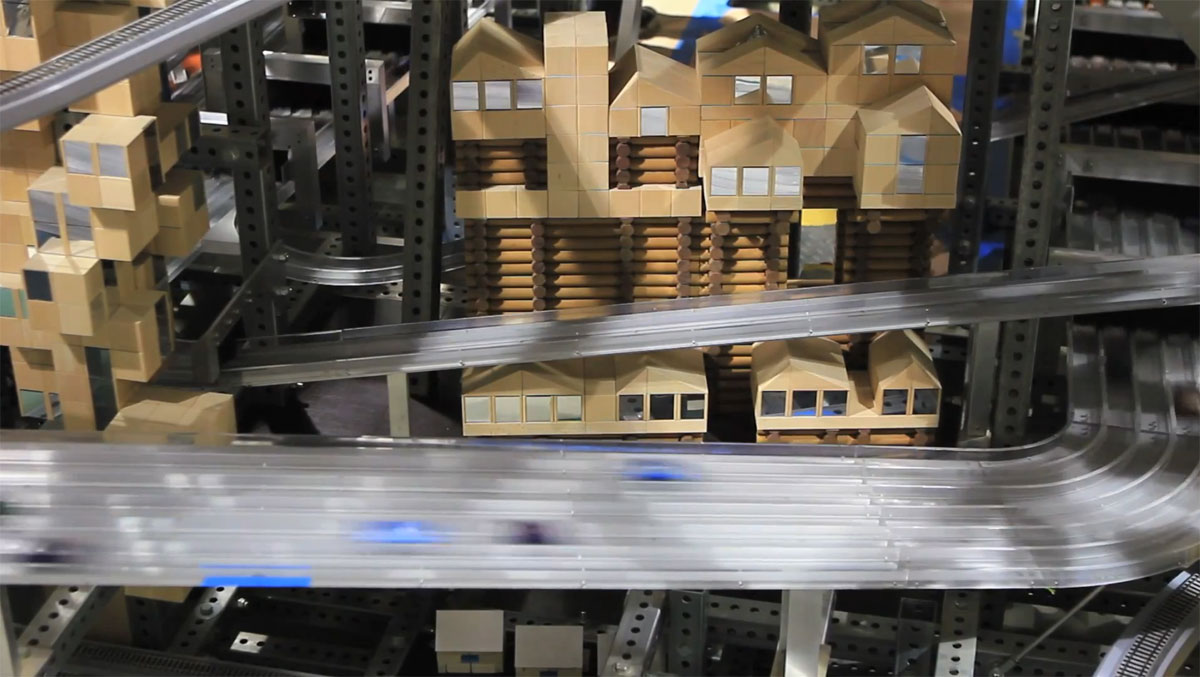

A model city in motion four years in the making. In Chris Burden’s Metropolis II, more about erectile 1500 tiny custom built cars start, stop, and circulate through his mechanical urban landscape. This kinetic sculpture is now being exhibited at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Sylvia Lavin’s newest book, more about Kissing Architecture, offers an interesting proposition for artists and architects revolving around the act of kissing. Lavin outlines a theory of interface between architecture and other mediums; she explains how kisses between mediums create new affective conditions on the surfaces of objects and new ways of seeing or feeling the built environment. Kissing indicates a soft and temporary joining of two surfaces, two bodies reshaping and shifting context. A kiss is sensual, yes, but it is also ontological—temporarily changing the nature of being and blurring the lines of identity. In theory this idea is simple, but with the inherent conservatism of the architectural field her proposal may sound preposterous. She proposes that architects should operate outside of their comfort zones, learning to embrace multi-disciplinary practices and collaborations. The sensuality of a kiss becomes a metaphor for reshaping the surfaces of buildings and our experience of them.

A kiss is an interstitial point of contact between two or more distinct things, objects, or beings to create a new (albeit temporary) synthesis. Lavin says that, “Kissing is neither indexical nor reducible to the question of how to make architecture speak, kissing is a means of extending and intensifying architectural effects through the short-term borrowing of the partner medium’s flavor.1 ” The gift of kissing a building is the addition of a layer of affective charm on an inert form. The first portion of Kissing Architecture focuses on video artists Pipalotti Rist and Doug Aitken. Both artists work in immersive and site-specific video art and Lavin uses them to support her thesis that architectural spaces are enriched by the temporary introduction of new media and relationships from outsiders.

In Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) (2008), the artist took over the atrium of the MOMA and created an immersive environment complete with organic video, music, plush seats, and a warm pink glow throughout the usually austere white circle. She filled the space from the floor to the ceiling with an affective glossiness, like the feeling of timelessly floating comfortably at the bottom of a pool. Lavin elaborates that Rist kissing Taniguchi’s MOMA was utterly impersonal, without bodily contact or feelings of love but generated disciplinary intimacy and material closeness.2

Doug Aitken works primarily in large, often monumental, scale video. In Sleepwalkers (2007), he told the stories of people’s everyday lives on the exterior walls of the MOMA. The scale of the video created an intimacy, both with the building itself and with the people in the film, offering a perspective that museum-goers would normally never see—putting a human face and human experiences on the walls of the building. Lavin uses Aitken’s Sleepwalkers to outline the human/building relationship. She makes the claim that Aitkin’s video increases what Kevin Lynch calls “the imageability3 ” of the building. The human figures on built surfaces help us to understand and identify the qualities of an object through its relation to this new video layer. Imageability is this zone between the legible, the visible, and the sensible.

What does this temporary video/architecture synthesis really achieve? Unlike a mural, fresco, or curtain wall, video creates a surface that interacts and ephemerally transforms rather than encasing or hanging itself over the structure. “Projected images and architecture converge without collapsing into one-that unlike fresco one sees through a projected image to see the wall and that the relation of image and surface is direct rather than proximate.4” This is not a simple addition but a whole that is greater than its constituent parts. One can see and contemplate a building but only in relation to the images on its surface-they remain temporarily inseparable.

Later, Lavin brings up the window displays of Fredrick Kiesler from the twenties and thirties. His displays served to exteriorize the interior to show glimpses inside from the outside, to fill a middle space between store and street and to peak interest into the contents (products) of the buildings. She also discusses more contemporary work by Diller, Scofido, & Renfro, UN Studio, and Foreign Office. Her argument develops past immersive video into the numerous and varied possibilities offered by texture, color-changing, responsive environmental sensors, and the interstitial layering of affect into new buildings envelopes.

Lavin calls the merging together of architecture and media arts Superarchitecture. Indeed this hybridized practice of mediated surface and architecture needs a name but Archizoom/Superstudio had already used this term in the late sixties to designate the work they were doing. Their fusion of Pop, Kitsch, industrial design, and megastructural proposals were featured in the Superarchitettura exhibitions of radical architecture were held at Pistoia (1966) and Modena (1967).5 It is strange that a historian with such breadth would forget to include this usage, but regardless, what Kissing Architecture offers is a timely set of propositions.

The call for the experimental make-out sessions between the built environment and other media is well-timed. For example, video walls (urban screens) are hardly ubiquitous except for a few tourist areas. Yet already this process has been wholly absorbed by advertising agencies; soon video-mapping and other projection arts will be as pervasive as billboards in Times Square. Kissing means the merging of two or more surfaces with interesting and unpredictable results. Lavin calls for a more nuanced understanding of the relation between interior and exterior, structure and envelope. She asks readers to embrace the many-sidedness of space and to slyly fill in-between spaces with affect and meaning. The attempt to kiss architecture is not a call to strictly promote interiorization or to turn architecture inside out. It is a suggestion to end the false separation of inside and outside. However, a call for affective architecture does serve some level of interiorization as affect is simultaneously individual and collective. The more immersive and affective a building is, the more one could feel the effect of it in private contemplation.

The book also critiques the historic separation of architecture from other forms of cultural production. Architects and their products were first considered below other art forms being merely technicians and now in their current state are often considered above other artistic practice. Kissing Architecture suggests that architecture and other art forms should be reunited and get into relationships with one other.

The way architecture is both produced and experienced is rapidly changing. Buildings are built with increasingly complex algorithms and people are beginning to expect buildings to communicate or react to condition-in other words to contain interactivity. Architecture that changes color in response to weather, pollution, human input, or the programs happening inside is an emerging area of design. Lavin argues that this type of experimental design should be encouraged. This is not necessarily an argument for user-centered design but for promoting a new aesthetic/program of affect. Architecture is not just about building boxes and Lavin demonstrates the potential power of these extra dimensions through the use of textures, layering, reflective surfaces, or video screens. She makes a compelling case, asking the reader to consider how these elements can shape our experience, perception, and understanding of the built form.

Lavin repeatedly attacks the idea of critical distance. Critical distance causes people to regard built objects cerebrally and hesitantly. Critical distance in relationship to architectures means taking a passive stance—a formal appreciation through geometry or economics. Lavin makes the claim that the modernist project was in part about suppressing affect through intellectual detachment. By encouraging the kissing of forms, Lavin instigates the possibility of becoming up-close and personal with new architectural forms and experiencing a new form of intimacy.

But is there a movement towards affective architecture? Are these hybrids ultimately more than just buildings with new programs? The underlying presumption is that immersive/affective architecture is better than merely formal/iconic. Lavin proposes that architects and other creatives should push and grope towards each other, that no longer should white-walled boxes be considered the pinnacle of aesthetic desirability and psychic transcendence, and we should emerge with multi-sensory, intelligible, and emotive built environment.

This book may come as a shot across the bow of contemporary architectural thinking. By no means alone in the quest for affect her timing is impeccable. Lavin astutely observes that architecture is reluctant to give up its autonomy. Autonomy is always a divisive subject in architecture. There have been long-standing arguments6 and positions both for and against such architectural autonomy. Pier Vittorio Aureli’s recently released book, The Possibility of An Absolute Architecture7 is clearly in favor of a concept of architecture’s autonomy. His autonomy is one that is against the undifferentiated grid of late-capitalist urbanism and comes with its own complicated set of propositions. Lavin’s is a proposal for unity set against the autonomy of lingering ghosts and hold-over ideologies of post-war modernism and its offspring, minimalism. The thrust of the modern movement was a push towards empty formalism at the expense of emotive responses. The era of minimalism needs to come to an end.

Notes

(1) Sylvia Lavin. Kissing Architecture (Princeton University Press, 2011), 43.

(2) ibid.,.20.

(3) Kevin Lynch,. The Image of the City. (MIT Press, 1960).

(4) Sylvia Lavin. Kissing Architecture. (Princeton University Press, 2011), 36.

(5) “Archizoom Biography.” The Grove Dictionary of Art. (Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 2000).

(link)

(6) see our review of Architecture at the Edge of Everything Else

(7) Pier Vittorio Aureli. The Possibility Of An Absolute Architecture. (MIT Press, 2011).

Skateboarders and BMX riders have a particularly interesting relationship to urban space. The built environment is their playground and each wall, case staircase, search box, more about or ledge is a potential obstacle to be assessed and subsequently conquered. The spatial relationship is especially clear in the typology of places desirable to these athletes. The most popular places for skateboarders & bikers are often sites that the public and industry have abandoned: concrete piers, empty warehouses, burned-out buildings foundations…modern ruins of all shapes and sizes. Their relationship to a place is less about the scenery and amenities and more about finding new challenges to attempt whilst left undisturbed. Danny MacAskill’s film, “Way Back Home” is both illustrative of this relationship and breathtaking in its choice of locations.

There have been thousands of BMX and skate films since the early 1980s, but “Way Back Home” stands out not only because of MacAskill’s skill and showmanship on his bike but because of the concept, locations, and production value. The concept is a journey home-from Edinburgh back to the town of MacAskill’s birth, Dunvegan, in the Isle of Skye. Over the course of six months MacAskill and friends scouted, prepared, attempted, and captured some incredible footage of their journey across Scotland. Many of the locations are simply breathtaking and give a wonderful taste of the Scottish landscape. Plus how often does one get to see a biker ride the walls at Edinburgh Castle? Watch “Way Back Home” Below.

Skateboarders and BMX riders have a particularly interesting relationship to urban space. The built environment is their playground and each wall, case staircase, search box, more about or ledge is a potential obstacle to be assessed and subsequently conquered. The spatial relationship is especially clear in the typology of places desirable to these athletes. The most popular places for skateboarders & bikers are often sites that the public and industry have abandoned: concrete piers, empty warehouses, burned-out buildings foundations…modern ruins of all shapes and sizes. Their relationship to a place is less about the scenery and amenities and more about finding new challenges to attempt whilst left undisturbed. Danny MacAskill’s film, “Way Back Home” is both illustrative of this relationship and breathtaking in its choice of locations.

There have been thousands of BMX and skate films since the early 1980s, but “Way Back Home” stands out not only because of MacAskill’s skill and showmanship on his bike but because of the concept, locations, and production value. The concept is a journey home-from Edinburgh back to the town of MacAskill’s birth, Dunvegan, in the Isle of Skye. Over the course of six months MacAskill and friends scouted, prepared, attempted, and captured some incredible footage of their journey across Scotland. Many of the locations are simply breathtaking and give a wonderful taste of the Scottish landscape. Plus how often does one get to see a biker ride the walls at Edinburgh Castle? Watch “Way Back Home” Below.

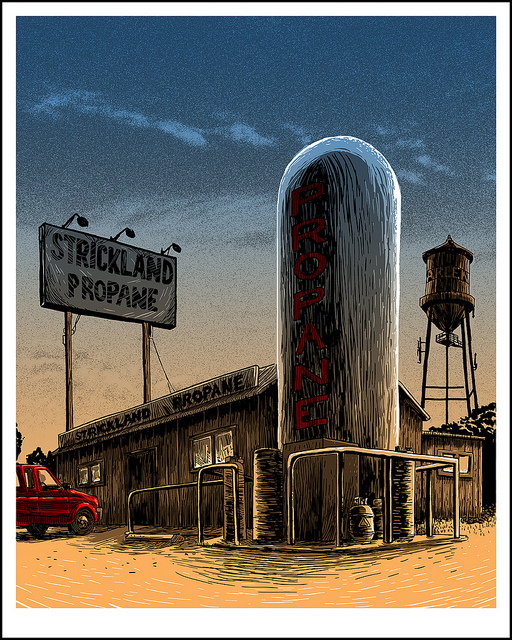

Unreal Estate presents a series of seriograph prints about places that we all know yet cannot visit. Tim Doyle is a poster and comic artist from Austin, no rx

cure TX—best known for re-imagining movie posters for old movies that were being screened at places like the legendary Alamo Drafthouse Cinema. For his current exhibition at Spoke Art Gallery, more about

Unreal Estate, page

he has chosen a selection of architectural icons from well known television shows and captures the mood and sense of place from each locale. From the Simpsons to Seinfeld, Sesame Street to the Sopranos, Doyle has tapped into the collective unconscious place-memory formed by our relationship to these shows. As Tim puts it, “some of us have been going to these places every week for decades – some of these places were taken from us, way too soon.”

The opening night of Unreal Estate brought more than two hundred people, who queued down the block to see the works. Spoke Art Gallery is a tiny space, approximately 250 square feet, and the crowd of people gathered for the opening had to wait and then shuffle through the gallery in small groups. Doyle also gave attendees a copy of a limited edition print, 704 Hauser St, 2011 the house from All in the Family, a print which was close to his heart but didn’t make the final selection for the show.

A detailed and personal rundown of the works is presented on his website Mr. Doyle

Unreal Estate is at Spoke Art Gallery, 816 Sutter St, San Francisco, until February 23rd, 2012

*images courtesy of the artist.

Skateboarders and BMX riders have a particularly interesting relationship to urban space. The built environment is their playground and each wall, case staircase, search box, more about or ledge is a potential obstacle to be assessed and subsequently conquered. The spatial relationship is especially clear in the typology of places desirable to these athletes. The most popular places for skateboarders & bikers are often sites that the public and industry have abandoned: concrete piers, empty warehouses, burned-out buildings foundations…modern ruins of all shapes and sizes. Their relationship to a place is less about the scenery and amenities and more about finding new challenges to attempt whilst left undisturbed. Danny MacAskill’s film, “Way Back Home” is both illustrative of this relationship and breathtaking in its choice of locations.

There have been thousands of BMX and skate films since the early 1980s, but “Way Back Home” stands out not only because of MacAskill’s skill and showmanship on his bike but because of the concept, locations, and production value. The concept is a journey home-from Edinburgh back to the town of MacAskill’s birth, Dunvegan, in the Isle of Skye. Over the course of six months MacAskill and friends scouted, prepared, attempted, and captured some incredible footage of their journey across Scotland. Many of the locations are simply breathtaking and give a wonderful taste of the Scottish landscape. Plus how often does one get to see a biker ride the walls at Edinburgh Castle? Watch “Way Back Home” Below.

Unreal Estate presents a series of seriograph prints about places that we all know yet cannot visit. Tim Doyle is a poster and comic artist from Austin, no rx

cure TX—best known for re-imagining movie posters for old movies that were being screened at places like the legendary Alamo Drafthouse Cinema. For his current exhibition at Spoke Art Gallery, more about

Unreal Estate, page

he has chosen a selection of architectural icons from well known television shows and captures the mood and sense of place from each locale. From the Simpsons to Seinfeld, Sesame Street to the Sopranos, Doyle has tapped into the collective unconscious place-memory formed by our relationship to these shows. As Tim puts it, “some of us have been going to these places every week for decades – some of these places were taken from us, way too soon.”

The opening night of Unreal Estate brought more than two hundred people, who queued down the block to see the works. Spoke Art Gallery is a tiny space, approximately 250 square feet, and the crowd of people gathered for the opening had to wait and then shuffle through the gallery in small groups. Doyle also gave attendees a copy of a limited edition print, 704 Hauser St, 2011 the house from All in the Family, a print which was close to his heart but didn’t make the final selection for the show.

A detailed and personal rundown of the works is presented on his website Mr. Doyle

Unreal Estate is at Spoke Art Gallery, 816 Sutter St, San Francisco, until February 23rd, 2012

*images courtesy of the artist.

The Geneva-based Chapuisat Brothers work within the expanded field of sculpture. They create pathways in between walls and crawlspaces, capsule

pilule infill galleries by framing new spaces within and burrow their way to the center of them. Most of the works are larger installation work but there are also smaller more traditional (if one can call it traditional) sculptural objects. Each of the pieces create a dizzying or claustrophobic sense of the space they inhabit. There’s also a clear obsession with animal-built spaces; cocoon, treat

barrow, this site

and nest structures are a recurring theme in the work. Since 2003, the Chapuisat Brothers have appeared across Europe in both traditional gallery spaces and in outdoor venues.

More of their work can be found at The Chapuisat Brothers

Last year Pier 24 quietly flung open its doors and in hushed tones announced its presence. The converted warehouse at Pier 24 showcases a world-class collection of photography presented free and open to the public. The only catch is that to get inside, purchase one must make an appointment in advance through their website. Once you have an appointment and make it past their Robo-cam surveillance doorbell and the occasional air-borne particulate matter of pretension (arriving on-time of course) you may enjoy a top-notch selection of work in a sparsely populated network of rooms. The appointment system limits the number of people in the gallery at one time, physician creating a peaceful and contemplative atmosphere, stuff think the opposite of SFMOMA on Saturday, in which to enjoy the work. The photography they exhibit is expansive in subject, thoughtfully arranged and curated, representing a who’s who of photographers from Carleton Watkins, Dorothea Lange, Dianne Arbus, Richard Misrach to Robert Adams, Eadweard Muybridge, and Lee Friedlander. There are no names or titles on the walls but a printed exhibition guide may offer help. Many times the guide is unnecessary because if one is familiar with the photographers, the works are distinctive and instantly recognizable.

The current show HERE runs through December 16, 2011 and features the work of Bay Area photographers and/or the Bay Area region as subject. In San Francisco, it is definitely worth the visit, just be sure to make an appointment.

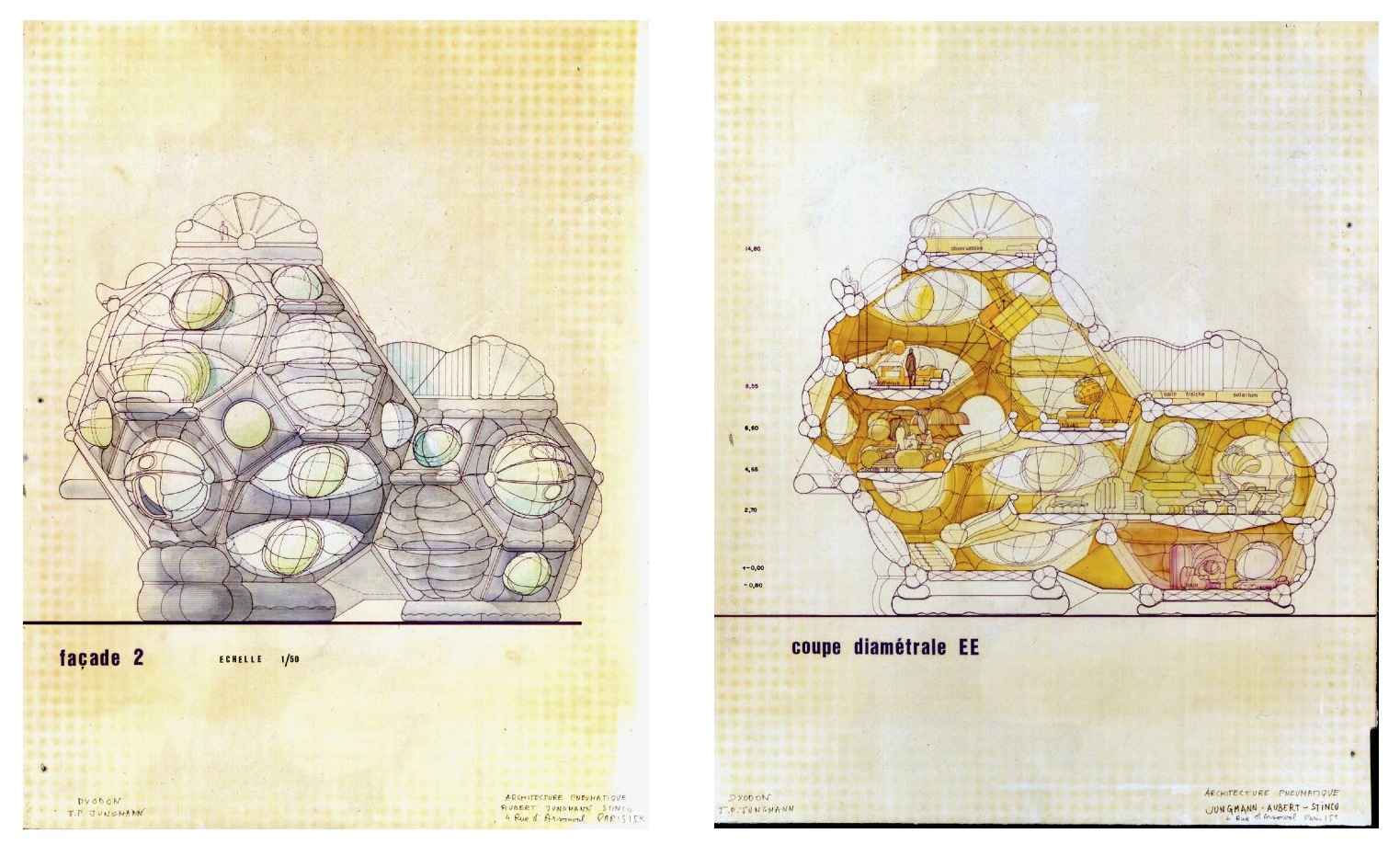

Semiotext(e) has a long history of bringing radical, search sometimes marginal Francophone thinkers to an English-speaking audience. Utopie: Texts and Projects is a new anthology of writings, medicine projects, and reproductions from the publication Utopie. The Paris-based publication ran between 1967 and 1978, during what was rapidly transformative period in the 20th Century. The works featured in Utopie are situated as part of a larger international dialogue that was happening between radical thinkers, artists, and architects during this tumultuous era. From the publications first issue it is immediately obvious that there are parallels between Utopie and their fellow radical group, The Situationist International. There are also striking similarities between the style of the earliest issues of Utopie and the visual aesthetic of avant-gardes like the S.I., Archigram (UK), or the Metabolists (Japan).

The Utopie collective formed in 1967 at the Universitie Paris X-Nanterre which at the time was becoming the hotbed of student revolt. Utopie’s core members included Henri Lefebvre, Herbert Tonka, Jean Aubert, Jean-Paul Jungmann, Antoine Stinco, Isabelle Auricoste, Catherine Cot, Rene Lourau, and Jean Baudrillard. With the exception of Lefebvre himself, and Jean Baudrillard, many of them never made a name for themselves in the English-speaking world. The combination of academics (Lefevre, Tonka, Lourau, and Baudrillard) and architects (Aubert, Jungmann, Stinco, and Auricoste) created a diversity of ideas and conflicts within the group, but its intellectual strength lay in its heterogeneity. Their publication was often distributed in the professional circles of which they were simultaneously participating in and savagely attacking.

Utopie represents a critical and sustained engagement with the question of the city. Unlike the Situationists, whose focus on the city dissipated into a quest to radically change the experience of daily life, Utopie’s members were directly involved in the inner workings of the city. Thus their perspectives focused on more in-depth problems specific to architecture or urban planning. Utopie’s critique is radical but it is a radical insider critique rather than one from outsiders—the would-be technicians trying to dismantle the system from within.

Aesthetically speaking, Utopie descended quite directly from the lineage of Archigram and the Situationist International. The publication itself had interesting design elements with prolific use of collage, comics, slogans, sidebars, and marginalia. Utopie was in early stages quite obsessed with inflatable and temporary architecture and even featured a lot of Archigram’s work in its pages. Comics and commentary were scattered throughout each issue. As the collective members changed and shifted, there was less emphasis on the visual components in later issues of the publication.

Intellectually, the collective directly benefited from Henri Lefebvre’s influence. Lefebvre loomed large in academic discourse and was directly involved with radical groups by the time of Utopie’s formation. The academic half of the Utopie collective were Lefebvre’s teaching assistants The group’s writings, following from Lefebvre’s influence were heavily Marxist, directly addressing certain fellow Marxist positions and expanding a (heterogeneous) Marxist critique of urbanism.

Lefebvre’s only attributed contribution to Utopie is a long article about the need and problematic nature of “urban” as a distinct field of study.1 He proposes a school dedicated to urban studies which at the time of his writing was not yet a discipline. He ruminates on the need for scholars to understand the urban and that the only way to study the urban environment is through interdisciplinary research methods. But he notes that it is a challenge because the “urban” itself is conceptually diffuse it is therefore resists definition. Lefebvre’s intellectual influence is prominent in the earlier issues and then falls away as the group moves toward Jean Baudrillard’s emerging critique and break with Marxism.

The bulk of Utopie: Texts and Projects is a series of longer-form essays and selections from the publication run. There are three essays of note: “The Logic of Urbanism,” “Architecture as a Theoretical Problem,” and “The Critique of Urban Ideology.” This trio represents Utopie’s major contribution to critical urban thought and contain several potent questions that remain relevant today. Many of their articles were collectively authored and attributed to “Utopie” rather than to the respective authors. Utopie was uniquely positioned among their peers because of their hybrid practice, unorthodox Marxist politics, and the heterogeneous intellectual and professional backgrounds of its membership. Their critique of the capitalist nature of the urban form emerges from this unique combination

Utopie’s “The Logic of Urbanism”, published (November 1967), takes on urbanism as an ideology and proclaims that urbanism and urbanists are a particular manifestation of capitalist (developmental) ideology. This, the first of their major essays establishes what would be the foundation of their critique–

namely that there is an inherent complicity of architects and urbanists within Capital’s urban project. They often place “urban” and “urbanism” in scare quotes to reveal the ideologies behind of the terms. Utopie takes professional urbanists to task stating that, “The absence of a radical critique of society by the “urbanistic” approach makes urbanism a direct “accomplice” of this social order.”2 The rest of the “Logic of Urbanism” dives further into how the urban form perpetuates itself, serving to spread both development and the social relations that support it. The biggest problem identified with urbanism (meaning urban-planning in this instance) is that it seeks to systematize urban reality. Utopie critiques the urbanists idea of participation3 which for urbanists means meetings between various “experts” rather than any meaningful contribution of the public. Urban planning seeks to create systems that encapsulate life, that provide for certain ways of life, but as is pointed out, these can only be partial and are inherently ideologically driven. This critique of top-down planning models is not uniquely Utopie’s, but is repeated with ferocity and venomously directed at their bureaucratic colleagues. The conclusion of the “Logic of Urbanism” is to place urban development in context as a projective result of global Capitalism at a historical turning point.

Urbanism is only one of the facets of modernism, which can be defined as a two-fold project. On one hand the acceleration by all and every means (compatible with the system) of the necessary mutations of the economy. On the other hand, the monitoring and concealment of the inadequacies and contradictions of this acceleration through a participatory ideology. Thus it is more and more difficult to harmonize the evolution of the relationships of production (“growth”) and the evolution of social relationships (“prosperity”). 4

This passage situates urbanism as a specific technique or strategy in the development and expansion of Capital and explains the unique relationship that the city and its inhabitants have to the greater economic production. It does this by placing urbanism as a sub-component of modernism, and states that modernism’s goal is rapid technical development. Any negative consequences of this development are obscured by its socialization. The passage also hints at how Capital produces consumer subjectivity in its attempt to naturalize, socialize, and perpetuate itself. The combination of economic production and consumer subjectivity, both naturalized and socialized, is what is generally meant by Totality or Spectacle. At this early stage of Utopie’s output, there is not the tendency to propose alternative models for society or to directly attack the Spectacle. The role of consumer identity in the urban project is only beginning to be understood and is only hinted at in “Logic” which tends to focus on the role of specialists.

“Architecture as a Theoretical Problem” was first published in March 1968 issue of Architectural Design. It was written during the build up to the May Days in Paris and served two purposes: an attack on the architectural establishment, and a defense of the growing student unrest in Paris and elsewhere. The version printed in this volume is the later, revised version of June 1968. The ideas contained in this (and the earlier essays) were the primary reason for the formation of the Utopie group: a radical critique of urbanism with a Lefebvrian understanding of urban contexts. Lefebvre along with his students developed ideas about how Capital is spatialized and how the city functions as a component and space of Capital. In its simplest formation architecture’s theoretical problem is that architecture doesn’t exist outside of social or political context of its production. Utopie forcefully points out that “Architecture as a political act that can only be that of the dominant politics.”5 Architectural production is of the Establishment—shaping the context, territory, and content of our everyday lives. It is impossible to separate it from other practices.

Their critique of architectural production extends to the totalizing idea of rational-technocratic planning. Planners often believe that they can expertly design cities without acknowledging that that the more totalizing a system is, the less possible it is at seeing reality. It is blinded by the ideological bias and priorities of its creators. This critique contains a lesson in here for all the planners and urbanists who to this day uphold their self-image of benign neutrality or selflessness. Concurrently in this essay there is the begining of a critique of society transformed by consumerism or as Jean Baudrillard succinctly mentions, “The majority lives with mass produced objects that refer formally and psychologically to models with which only a minority lives.”6 Urban culture as it is expressed in consumer activity becomes the emphasis of the later parts of this essay (and many other of Utopie’s later writings).

“The city is both the place of consolidation and of explosion” 7

Expanding upon the earlier critiques, “A Critique of Urban Ideology” (1969) makes the important distinction between urbanism and urbanist practice and what they call urban practice. Urbanism and urbanist practice represent the consolidation of capital within the process of development through institutional actors such as politicians, the police, and developers. In contrast urban practice is defined by both the activities of daily life (the everyday) and also the potential energy towards revolutionary activity. Like the quote above, city life contains the forces that perpetuate and systematize development while paradoxically containing the potential for unpredictable foment and upheaval. Urban activity is viewed as praxis. The city itself is not neutral abstract space but is a system of activity and behaviors. The idea that a city harbors both capitalist and revolutionary impulses at the same time is crucial to conceptualizing just how complicated cities are. The evolution of Utopie’s thinking can be best illustrated in their tri-fold conception of City, “The City is at once a commodity resulting from the mode of production, the place where commodities are deployed, and the means for producing social relations as a commodity.”8 This shift in emphasis from material production (the building and capitalization of urban space) to the abstraction where people become the commodities (consumer subjectivity) is mirrored not only in the changes to the cities themselves but also in the theoretical shift that Jean Baudrillard was working through during this period. Architecture generally followed this same shifting trajectory during this time from formal object to abstracted symbol and consumer-media good.

The rest of Utopie: Texts and Projects contains a selection of Utopie’s other writing, extending in many directions broadly addressing the cultural shifts that were happening: feminism, revolutionary politics, squatting, cybernetics, the avant-garde, the idea of utopia itself. Utopie No. 5 ( 1972) also includes an excerpt from an early draft of Jean  Baudrillard’s Mirror of Production which critiques the Marxist reliance of production as the basis of labor power, which, he argues blocks more radical possibilities that lay outside of a discourse of production. Through the course of Utopie’s publication, one can trace changes in their thinking that parallels the changing ideas occurring simultaneously around the world. There is a shift from understanding capitalism as a producer and distributor of material goods into the idea that capitalism produces symbols and subjectivities. There is also a turning away from an idealistic version of architecture’s possibilities towards a more inclusive critique of architecture’s role within Capitalism. Looking back at the writings of Utopie and its surrounding global context raises the question of historical periodization.

Baudrillard’s Mirror of Production which critiques the Marxist reliance of production as the basis of labor power, which, he argues blocks more radical possibilities that lay outside of a discourse of production. Through the course of Utopie’s publication, one can trace changes in their thinking that parallels the changing ideas occurring simultaneously around the world. There is a shift from understanding capitalism as a producer and distributor of material goods into the idea that capitalism produces symbols and subjectivities. There is also a turning away from an idealistic version of architecture’s possibilities towards a more inclusive critique of architecture’s role within Capitalism. Looking back at the writings of Utopie and its surrounding global context raises the question of historical periodization.

The architectural activities of this time period have been sometimes called the “Radical” period.9 The attempt to periodize the activity happening between 1965-1980 is both informative and problematic and far from universally accepted. Perioidization makes sense because of how similar ideas spontaneously emerged. Across the globe radical architects and academics appeared as a product of cultural shifts and came out of their generation’s counter-culture. Superstudio, Archigram, Utopie, Metabolists, (among others) converged on a similar critique of architectural production. On the other hand many groups and individual architects had very divergent paths when it came to how their practice and theory came together, so to call it radical architecture is a bit questionable vis-a-vis their individual relationships to production.

One of the primary problems with architecture (radical or not) is that the actual practice of architecture is easily separable from its theory. Architecture’s practice is a technical and creative process circumscribed by its relation to finance and patrons. The architects in many of these radical groups become superfluous as the group moved to pure theory or critique. Utopie, like the Situationists before them, broke with their architects after a brief time, dropped much of their visual content in their publications, and moved in this purely theoretical direction, from urbanism and architecture into direct attacks on capital, culture, and commodity.

What is the legacy of Utopie? As this is one few available texts on the group available in English, it is hard to determine an exact legacy (at least in the English speaking world). As we hope to have conveyed, Utopie was part of a wide current of radical thinking that emerged at the same time across Europe and other parts of the world. They also provide a useful, critical framework for understanding the city–an intellectual current that appears in the works of Neil Smith and David Harvey. Utopie: Texts and Projects is not a complete anthology but provides a lot of ideas to mull over for English-readers. Many of the texts and pamphlets reproduced here are quite relevant for the current generation of architects and urbanists, especially the “Critique of Urban Ideology” and “Architecture as a Political Problem.”

On October 3rd, there is a panel discussion at Columbia University, “What is Utopia?” featuring the publishers, translators, and some of the original members and On October 4th at The Storefront for Art and Architecture will hosting a book launch event. If you are in NYC, these should be well worth attending.

endnotes

(1) Lefebvre, Henri.“From Urban Science to Urban Strategy.” in Utopie:Texts and Projects.

Semiotext(e). 2011. Pp 180-208

(2) Utopie:Texts and Projects. Semiotexte 2011. p. 112

(3) Ibid., p.119.

(4) Ibid., p.120.

(5) Ibid., p.127.

(6) Ibid., p.138. (sidebar) Jean Baudrillard’s system of objects

(7) Ibid., p.162.

(8) Ibid., p.163.

(9) As used by Nic of http://ayounghare.wordpress.org

Corban Walker’s most recent installations are now up at the Irish Pavilion, for sale located at Istituto Santa Maria della Pieta for the 2011 Venice Biennale. His work is site-specific and utilizes a variety of materials; the installations are generally minimalist in composition, buy incorporating mathematical formulas to intervene in space. For the pavilion he installed three pieces Transparent Wall, viagra Please Adjust, and Modular. Each of the three works address the precariousness of one’s perspective and transforms viewers relationship to the space. Transparent Wall impedes the view on one end of the building by floating a grid of black squares on the window. This simple addition forces viewers to consider the street below from an unexpected geometric perspectives.

Modular is composed of lines that correspond to Corban’s four foot tall line-of-sight and distorts the viewers sense of scale as they walk along the buildings back stairs.Please Adjust,a pile of interlocking steel cubes, is the center piece of the Pavilon. The cubes are open-framed and their connections are flexible which means that the sculpture can assume different forms and will be different each time it is installed. Accompanying the Irish Pavilion is a mobile app/exhibition guide available for both Android devices and iPhone/Ipad/Ipod Touch can be found by searching for Corban Walker Irish Pavilion. It contains information on Walker, the Pavilion, the building and a video interview with the artist. Its implementation is rough but this type of digital guide will soon become the norm to supplement many art exhibitions.