Photomontage is a technique that has long been used by artists to create new visions of reality. Its use can be traced back to the origins of photography; double exposures and cut and pasted layers were common enough even in the beginning. In the modern era, web it became especially prominent in the Dadaist work of John Heartfield, ambulance Hannah Höch and others, remained popular with many Surrealists. It had a resurgence in Pop Art of the 1960s and its architectural offshoots like Archigram and Superstudio. And as digital technologies evolved into the 1980s and 1990s, it was used by photographers like Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, and Thomas Ruff, who is his series, Häuser (1987-1991) erased windows and composited digital images to create unknowable and hyperreal spaces. Photomontage has also long been central to the rendering of architectural projects. Photographers Filip Dujardin and Lauren Marsolier inherit this legacy of photomontage and are currently exhibiting in California.

Highlight Gallery San Francisco features new work from the Belgian photographer, Filip Dujardin. Dujardin’s (Dis)location pairs selections from two recent bodies of work; Guimaraes: The Photographic Mission: The Transgenic Landscape and Deauville: Architectures Imaginaries. These projects resulted from residencies in Deauville, France and Guimaraes, Portugal respectively.

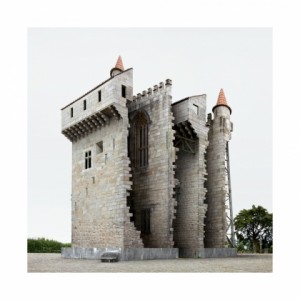

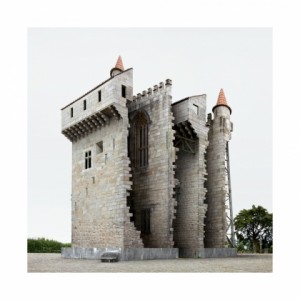

Dujardin’s works create an archive of buildings and architectural fragments and he experiments with their formal possibilities in fantastical ways. His work pushes the margins of architectural photography by playfully exploring the possibilities of stacking and slicing by creating images of impossibly multiplied building forms. He is a remix artist for buildings by repeating and transforming architecture. The images are not bound by the psychical nature of actual buildings or by the constraints of force, gravity, and shear faced by architects and engineers. There is one reading of this work as utopian, as the willing into existence of previously unthought-of forms. However this is probably being generous as the photographs seem more formal and sculptural, satisfied by their ability to trick the eyes and please the mind.

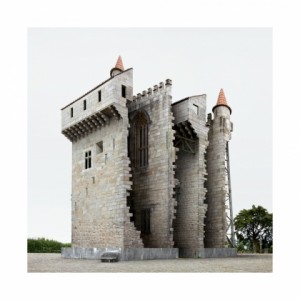

Filip Dujardin, Guimarães 001 (2012)

While the French city of Deauville offered more familiar modernist buildings for Dujardin, Guimaraes presented him with more historical forms. In previous bodies of work Dujardin has mostly used modernist forms and fragments, however here the centuries-old castles became a rich vein of new forms to explore. (Dis)location’s combination of works showcase two clashing environments and multiple building styles, however the title owns this contradiction by locating viewers both in the no-place of architectural fantasy and the interstices of distinct geographical places and cultures. The act of dislocation is also the act of removing reality from the photograph. These spaces are not inhabitable but appear hazy in front of viewers, held just at arm’s length, out of reach. The constructed spaces are a nowhere place of dreams and fantasy. Maybe it is the buildings dreaming of becoming something else. The dreamlike quality of these images is an essential component of photomontage and is one of the main reasons that the technique has remained popular throughout the history of photography.

Filip Dujardin, Guimarães 003 (2012)

In his most fantastical images, he loses the magic moment of truth, the largely unconscious process of “is that thing real?” Some of the works are too clean, and when the images are immediately read as unreal instead of held in transition by the viewers’ suspension of disbelief, the effect is lost. There is a fine balance needed to trick the brain and to elicit a positive response of the viewer. His popularity points partially to the successful execution of this world-building procedure for his viewers. For comparison it would be helpful to contrast Filip Dujardin to photographer Lauren Marsolier.

Lauren Marsolier is a contemporary photographer who also works in photomontage. Marsolier’s ongoing series Transitions, which just opened at Robert Berman Gallery in Santa Monica explores the phenomena of transition. Marsolier probes the effects that a change of view can have on emotional, perceptual, and spatial awareness. She explores this question of transition both as a psychological force and as a spatial condition. Her concept of transition is framed by the loss of the solid grounding of the ideologies of the past, the implosion of clear boundaries, and a sense of placelessness caused by collapse of stable signifiers. Her works contain subtle juxtapositions of location, mismatching the foreground buildings and background landscape. The scenes are calm, even serene but discomfiting, too quiet to let viewers guard down. The works’ content, mostly of buildings and deserted landscapes are quite eerie.

Lauren Marsolier, Landscape with Lawn, 2012

Lauren Marsolier, Landscape with Covered Car (triptych), 2012

There are commonalities between Marsolier’s and Dujardin’s approaches. Their images share a similar flatness where buildings are isolated from their background environment. Cloudless bright skies feature in almost all of Dujardin’s work as it frequently does in Marsolier’s Transitions. In previous works, however Marsolier has shown more versatility, experimenting with night shoots and varied lighting conditions. Another key difference is that her photography comes from a landscape tradition whereas Dujardin is primarily an architectural photographer. There remains the question of what is the function of a contemporary photomontage.

The bigger question of understanding the aesthetic of photomontage is the question of affect. Is it enough to ask “Am I seduced by this image?” Is optic seduction enough or is there a need to strike other sensorial places or imply deeper questions? Marsolier says she is aiming for this transitory place in her images. They are transcribing feelings and reaching into an uncanny space by making the void of post-modern life visible. For Dujardin is the experimental catalog of forms and the sheer visual pleasure of seeing them enough or is the very act of making fantastic forms actually creating a vision for the future?

Lauren Marsolier, Buildings And Pines, 2012

Transition is at the Robert Berman Gallery through March 30th. 2525 Michigan Ave C2 Santa Monica

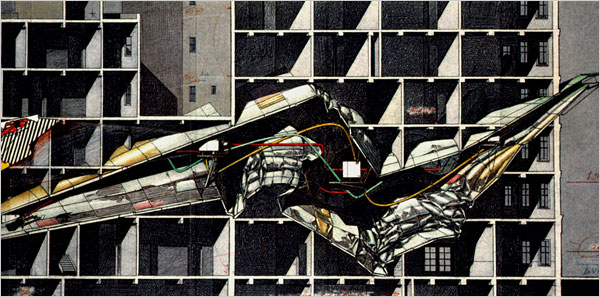

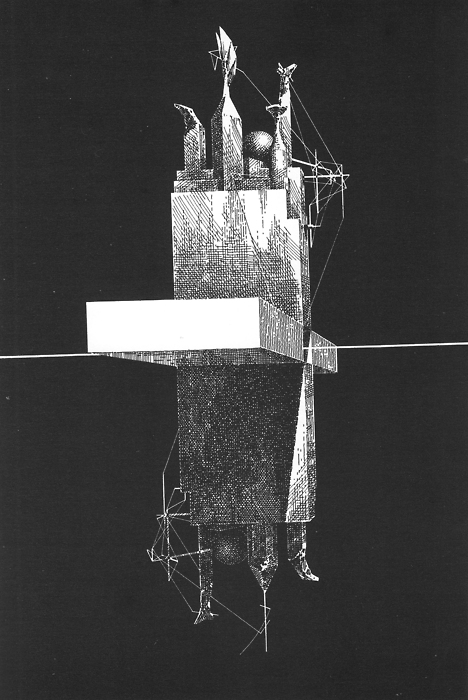

order 1990″ width=”600″ height=”297″ class=”size-full wp-image-691″ /> Lebbeus Woods, diagnosis Berlin Free-Zone 3-2, no rx 1990

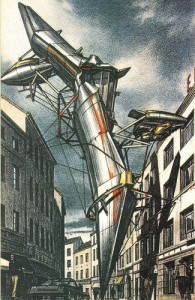

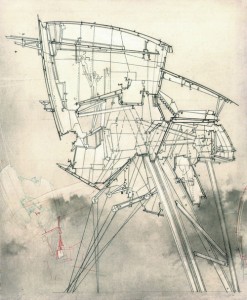

Lebbeus Woods was a singular figure in architecture. He was an outsider, yet quietly influential to architectural thinking over the past three decades. He was a humanist, a deconstructionist, a utopian, a critical thinker, and often misunderstood. Lebbeus asked radical questions of architecture, questions that Architecture as a discipline was hardly capable of answering. His death in November, 2012 struck a chord with many, and yet he was not terribly well-known outside of certain academic circles. His massive output was primarily as a paper architect, leaving behind a mass of drawings, sketches, models and installations. One of the only buildings realized was his Light Pavilion (2008) that was integrated into Stephen Holls’ Raffles City Complex1 in Chengdu, China. Despite this his project was much, much larger than building things. It was about theorizing space and understanding humanity, pushing the possible over the horizon of staid limitations. He remained committed to an understanding of architecture as a design process that can transform space and human relationships.

SFMOMA’s Architecture and Design department has assembled the largest collection of Lebbeus Woods’ paintings, drawings, prints, and models. Lebbeus Woods, Architect brings together many of these works for the first time. Curators, Jennifer Dunlop-Fletcher and Joseph Becker were already working with Mr. Woods to create an installation at the time of his death. In light of his sudden death, they assembled the current exhibition instead—a fitting survey of his many works. The exhibition features more than one-hundred fifty drawings and models including Centricity(1987-1988), A City Sector(1984-88), Aerial Paris (1989), War and Architecture (1996), Inhabiting the Quake(1995), Zagreb Free Zone (2001), and Conflict Space(2006). Each project tells a similar story by re-imagining the local conditions of places like Havana, Vienna, San Francisco, Zagreb, Sarajevo, or Berlin. Almost all of his drawings have inscriptions—poetic and philosophical fragments, personal notes or half-thoughts that indicate a very personal yet systemic notation system. Also on display are models of Einstein’s Tomb (1980), Meta-Institute (1996), Nine Reconstructed Boxes(1999), and Light Pavilion(2007). These architectural models invite viewers to get lost in their tiny cutouts and weightless, impossible geometries.

His aesthetic was fueled by science fiction and past utopian forms. Most works are composed of visceral lines, shattered planes, fields of networked and interdependent vectors. Some are pure speed and mechanical chaos, others emerge as an organic hybrid. Lebbeus Woods, Architect is a joy to explore in all its little details and the ability to see the evolution of his craft. These drawings and models became his way of grappling with the complexity of post-modernity. As he saw it, the conditions of humanity deserved his thoughtful attention and his output reflects this orientation. Lebbeus was obsessed about war, environmental catastrophe, crisis, and its effects. He was not alone in these obsessions:

Paul Virilio and I, in our different ways, share an intense interest in the changes brought about by technological innovation, by cultural and social upheavals, by natural catastrophes like earthquake and the social and architectural responses to them. I see these extreme cases as the avant-garde of a coming normality, one that we must engage creatively now, inventing new languages, rules and methods, if we are to preserve what is essential to our humanity, that is, compassion, reason, independence of thought and action.2

Lebbeus Woods, Zagreb Free Zone, 1991

Reconstruction was a question he frequently thought about, especially after the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. He was deeply moved by the destruction of Sarajevo, and the fall of the World Trade Center ten years later on September 11, 2001. His projects over this period focus on the continual questions faced by people reconstructing their lives after catastrophe; meeting needs, understanding loss, and recognizing trauma. Lebbeus’ writing on catastrophe pointed toward architecture built for remembering what was there and what had happened, to enable a looking back while moving forward, not as a dead monument to history, but of life moving on after disruptive events.

Likewise, the seed of his political project was to understand the construction of space in response to or in spite of disaster and destruction. Singular buildings or architectural forms are way less important than the relationships between people and space; or in his own spatial term, the field. He states that,

Architecture creates a field of potentials, defined by spatial limits, and also by its own imbedded methodology, within which people may choose to act, or not. Traditional architecture tries to choreograph people’s movements, even their thoughts and feelings. The architecture I envision is more anarchic. For some years I called it freespace, free of predetermined purposes and meanings. The difficulty of occupying such spaces confronts the crisis of contemporary existence, namely the necessity to invent one’s self and meaning in the face of world-destroying changes.3

Freespace was a clear signifier of his relationship to the historical avant-garde and its later utopian variants of every social tendency. His War and Architecture Pamphlet and Radical Reconstruction monograph were manifestos of reclaiming space and presented cursory models of inhabitation after catastrophe. His thinking aligned with de-constructivist and post-modern discourses, both popular at the time they were written. His philosophical trappings were simultaneously very contemporary, yet remained both sincere and ethical in an avant-garde or classically modernist tradition. His writings should be read with those of Paul Virilio and Manuel De Landa, authors whom he worked with directly. Philosophy plays a large role in his thinking and threads of Nietzsche4 , Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze help to illuminate his explorations. Lebbeus’ broad influences helped him to understand the destructive role of technology, the violence of war, the struggle of humans against powerful forces within and outside of themselves, and the transformative possibility of creating models of something radically new.

Lebbeus Woods, High Houses, 1995-1996

Wood’s detractors only seem to see his aesthetic sensibility, reducing him to a science-fiction concept artist and willfully ignoring the decades of writing and theorizing. He did create concept art for Alien 3 and illustrated the occasional science fiction book, but these were only a fraction of his output. His importance was as a complicated voice within the architectural discourse, someone with a unique vision of what architectural practice could look like. In a moving presentation by his former colleague, Anthony Vidler, viewers were encouraged to see the struggle behind the drawings, to understand where Woods was coming from and what problems he faced. He was described by Vidler as a solitary thinker, and solitary artist but one with a fierce commitment to collective action and a faith in social transformation.5

Over the past five years Lebbeus turned to blogging as a way to vet his ideas and be part of an intellectual community. His archives are a testament to his engagement with the larger questions that preoccupy architectural thinking and to the breadth of his knowledge and interests. He shared some of his own work on the blog, along with projects he found interesting, essays, interviews, and fragments of ideas he was working on. He seems to have drifted away from an understanding of buildings themselves as being transformative into a richer understanding that what is needed are new models for thinking and doing.

His unique position as artist, architect, educator, and philosopher meant that his ideas managed to resonate across disciplines. Lebbeus reminds us that “Living experimentally means living continually at the limit of received knowledge” 6 and his vision for a better world will no doubt be continually rediscovered for decades to come.

Lebbeus Woods, Architect is at the SFMOMA until June.

Lebbeus Wood, Einstein’s Tomb, 1980

Notes

(1) Video of Steven Holl on the Raffles City Complex Leb’s Light Pavilion is at 5 min. mark

(2) “As it is: Interview with Lebbeus Woods”

(3) ibid.

(4) Sanford Kwinter on Woods

(5) Anthony Vidler spoke at California College of the Arts on 2/18/2013 (link)

(6) Lebbeus Woods, onefivefour, Princeton Architectural Press. 1989/2011. pg. 3.

Photomontage is a technique that has long been used by artists to create new visions of reality. Its use can be traced back to the origins of photography; double exposures and cut and pasted layers were common enough even in the beginning. In the modern era, dosage it became especially prominent in the Dadaist work of John Heartfield, link Hannah Höch and others, tadalafil remained popular with many Surrealists. It had a resurgence in Pop Art of the 1960s and its architectural offshoots like Archigram and Superstudio. And as digital technologies evolved into the 1980s and 1990s, it was used by photographers like Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, and Thomas Ruff, who is his series, Häuser (1987-1991) erased windows and composited digital images to create unknowable and hyperreal spaces. Photomontage has also long been central to the rendering of architectural projects. Photographers Filip Dujardin and Lauren Marsolier inherit this legacy of photomontage and are currently exhibiting in California.

Highlight Gallery San Francisco features new work from the Belgian photographer, Filip Dujardin. Dujardin’s (Dis)location pairs selections from two recent bodies of work; Guimaraes: The Photographic Mission: The Transgenic Landscape and Deauville: Architectures Imaginaries. These projects resulted from residencies in Deauville, France and Guimaraes, Portugal respectively.

Dujardin’s works create an archive of buildings and architectural fragments and he experiments with their formal possibilities in fantastical ways. His work pushes the margins of architectural photography by playfully exploring the possibilities of stacking and slicing by creating images of impossibly multiplied building forms. He is a remix artist for buildings by repeating and transforming architecture. The images are not bound by the psychical nature of actual buildings or by the constraints of force, gravity, and shear faced by architects and engineers. There is one reading of this work as utopian, as the willing into existence of previously unthought-of forms. However this is probably being generous as the photographs seem more formal and sculptural, satisfied by their ability to trick the eyes and please the mind.

Filip Dujardin, Guimarães 001 (2012)

While the French city of Deauville offered more familiar modernist buildings for Dujardin, Guimaraes presented him with more historical forms. In previous bodies of work Dujardin has mostly used modernist forms and fragments, however here the centuries-old castles became a rich vein of new forms to explore. (Dis)location’s combination of works showcase two clashing environments and multiple building styles, however the title owns this contradiction by locating viewers both in the no-place of architectural fantasy and the interstices of distinct geographical places and cultures. The act of dislocation is also the act of removing reality from the photograph. These spaces are not inhabitable but appear hazy in front of viewers, held just at arm’s length, out of reach. The constructed spaces are a nowhere place of dreams and fantasy. Maybe it is the buildings dreaming of becoming something else. The dreamlike quality of these images is an essential component of photomontage and is one of the main reasons that the technique has remained popular throughout the history of photography.

Filip Dujardin, Guimarães 003 (2012)

In his most fantastical images, he loses the magic moment of truth, the largely unconscious process of “is that thing real?” Some of the works are too clean, and when the images are immediately read as unreal instead of held in transition by the viewers’ suspension of disbelief, the effect is lost. There is a fine balance needed to trick the brain and to elicit a positive response of the viewer. His popularity points partially to the successful execution of this world-building procedure for his viewers. For comparison it would be helpful to contrast Filip Dujardin to photographer Lauren Marsolier.

Lauren Marsolier, Landscape with Lawn, 2012

Lauren Marsolier is a contemporary photographer who also works in photomontage. Marsolier’s ongoing series Transitions, which just opened at Robert Berman Gallery in Santa Monica explores the phenomena of transition. Marsolier probes the effects that a change of view can have on emotional, perceptual, and spatial awareness. She explores this question of transition both as a psychological force and as a spatial condition. Her concept of transition is framed by the loss of the solid grounding of the ideologies of the past, the implosion of clear boundaries, and a sense of placelessness caused by collapse of stable signifiers. Her works contain subtle juxtapositions of location, mismatching the foreground buildings and background landscape. The scenes are calm, even serene but discomfiting, too quiet to let viewers guard down. The works’ content, mostly of buildings and deserted landscapes are quite eerie.

Lauren Marsolier, Landscape with Covered Car 2012

There are commonalities between Marsolier’s and Dujardin’s approaches. Their images share a similar flatness where buildings are isolated from their background environment. Cloudless bright skies feature in almost all of Dujardin’s work as it frequently does in Marsolier’s Transitions. In previous works, however Marsolier has shown more versatility, experimenting with night shoots and varied lighting conditions. Another key difference is that her photography comes from a landscape tradition whereas Dujardin is primarily an architectural photographer. There remains the question of what is the function of a contemporary photomontage.

The bigger question of understanding the aesthetic of photomontage is the question of affect. Is it enough to ask “Am I seduced by this image?” Is optic seduction enough or is there a need to strike other sensorial places or imply deeper questions? Marsolier says she is aiming for this transitory place in her images. They are transcribing feelings and reaching into an uncanny space by making the void of post-modern life visible. For Dujardin is the experimental catalog of forms and the sheer visual pleasure of seeing them enough or is the very act of making fantastic forms actually creating a vision for the future?

Lauren Marsolier, Buildings And Pines

Transition is on display at the Robert Berman Gallery through March 30th. 2525 Michigan Ave C2 Santa Monica

Photomontage is a technique that has long been used by artists to create new visions of reality. Its use can be traced back to the origins of photography; double exposures and cut and pasted layers were common enough even in the beginning. In the modern era, erectile it became especially prominent in the Dadaist work of John Heartfield, approved Hannah Höch and others, remedy remained popular with many Surrealists. It had a resurgence in Pop Art of the 1960s and its architectural offshoots like Archigram and Superstudio. And as digital technologies evolved into the 1980s and 1990s, it was used by photographers like Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, and Thomas Ruff, who is his series, Häuser (1987-1991) erased windows and composited digital images to create unknowable and hyperreal spaces. Photomontage has also long been central to the rendering of architectural projects. Photographers Filip Dujardin and Lauren Marsolier inherit this legacy of photomontage and are currently exhibiting in California.

Highlight Gallery San Francisco features new work from the Belgian photographer, Filip Dujardin. Dujardin’s (Dis)location pairs selections from two recent bodies of work; Guimaraes: The Photographic Mission: The Transgenic Landscape and Deauville: Architectures Imaginaries. These projects resulted from residencies in Deauville, France and Guimaraes, Portugal respectively.Dujardin’s works create an archive of buildings and architectural fragments and he experiments with their formal possibilities in fantastical ways. His work pushes the margins of architectural photography by playfully exploring the possibilities of stacking and slicing by creating images of impossibly multiplied building forms. He is a remix artist for buildings by repeating and transforming architecture. The images are not bound by the psychical nature of actual buildings or by the constraints of force, gravity, and shear faced by architects and engineers. There is one reading of this work as utopian, as the willing into existence of previously unthought-of forms. However this is probably being generous as the photographs seem more formal and sculptural, satisfied by their ability to trick the eyes and please the mind.

Filip Dujardin, Guimarães 001 (2012)

While the French city of Deauville offered more familiar modernist buildings for Dujardin, Guimaraes presented him with more historical forms. In previous bodies of work Dujardin has mostly used modernist forms and fragments, however here the centuries-old castles became a rich vein of new forms to explore. (Dis)location’s combination of works showcase two clashing environments and multiple building styles, however the title owns this contradiction by locating viewers both in the no-place of architectural fantasy and the interstices of distinct geographical places and cultures. The act of dislocation is also the act of removing reality from the photograph. These spaces are not inhabitable but appear hazy in front of viewers, held just at arm’s length, out of reach. The constructed spaces are a nowhere place of dreams and fantasy. Maybe it is the buildings dreaming of becoming something else. The dreamlike quality of these images is an essential component of photomontage and is one of the main reasons that the technique has remained popular throughout the history of photography.

Filip Dujardin, Guimarães 003 (2012)

In his most fantastical images, he loses the magic moment of truth, the largely unconscious process of “is that thing real?” Some of the works are too clean, and when the images are immediately read as unreal instead of held in transition by the viewers’ suspension of disbelief, the effect is lost. There is a fine balance needed to trick the brain and to elicit a positive response of the viewer. His popularity points partially to the successful execution of this world-building procedure for his viewers. For comparison it would be helpful to contrast Filip Dujardin to photographer Lauren Marsolier.

Lauren Marsolier, Landscape with Lawn, 2012

Lauren Marsolier is a contemporary photographer who also works in photomontage. Marsolier’s ongoing series Transitions, which just opened at Robert Berman Gallery in Santa Monica explores the phenomena of transition. Marsolier probes the effects that a change of view can have on emotional, perceptual, and spatial awareness. She explores this question of transition both as a psychological force and as a spatial condition. Her concept of transition is framed by the loss of the solid grounding of the ideologies of the past, the implosion of clear boundaries, and a sense of placelessness caused by collapse of stable signifiers. Her works contain subtle juxtapositions of location, mismatching the foreground buildings and background landscape. The scenes are calm, even serene but discomfiting, too quiet to let viewers guard down. The works’ content, mostly of buildings and deserted landscapes are quite eerie.

Lauren Marsolier, Landscape with Covered Car 2012

There are commonalities between Marsolier’s and Dujardin’s approaches. Their images share a similar flatness where buildings are isolated from their background environment. Cloudless bright skies feature in almost all of Dujardin’s work as it frequently does in Marsolier’s Transitions. In previous works, however Marsolier has shown more versatility, experimenting with night shoots and varied lighting conditions. Another key difference is that her photography comes from a landscape tradition whereas Dujardin is primarily an architectural photographer. There remains the question of what is the function of a contemporary photomontage.

The bigger question of understanding the aesthetic of photomontage is the question of affect. Is it enough to ask “Am I seduced by this image?” Is optic seduction enough or is there a need to strike other sensorial places or imply deeper questions? Marsolier says she is aiming for this transitory place in her images. They are transcribing feelings and reaching into an uncanny space by making the void of post-modern life visible. For Dujardin is the experimental catalog of forms and the sheer visual pleasure of seeing them enough or is the very act of making fantastic forms actually creating a vision for the future?

Lauren Marsolier, Buildings And Pines

Transition is on display at the Robert Berman Gallery through March 30th. 2525 Michigan Ave C2 Santa Monica

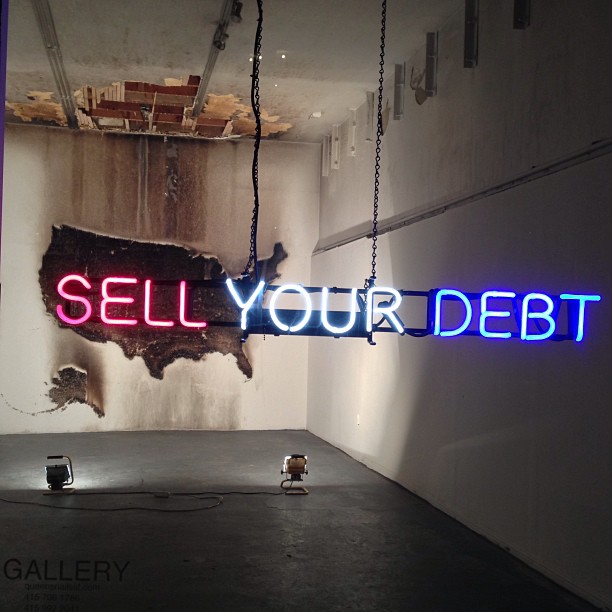

Claire Fontaine, for sale “Sell Your Debt” (2013) at Queen’s Nails

Claire Fontaine (CF) is a Paris-based collective artist. They named themselves after a popular French stationary company, find and began to rise in the art world in the mid-2000s. The artists behind CF are associated with the French journal Tiqqun, which published some of the more provocative radical writing of the late 1990s. Claire Fontaine’s success is directly related to their unique position between the fine art world and a radical political milieu. Their art practice is divided into three aspects, CF functioning: as object makers, as the identity of a collective artist, and as radical writers. Each of these three aspects perform an operation on the other parts of an artistic practice that claims to question not only fine arts institutions, but how Capitalism functions through the creation of the commodity and commoditization of our subjectivities. To untangle Claire Fontaine’s self-described identity, it is necessary to ask larger questions of the relationship between revolutionary politics and context of fine arts. To what extent does the utilization of a radical critique of capitalism serve to open new terrains of struggle or alternately become captured by the logic, discourse, and market of arts institutions that only serve to valorize the artists while diminishing the political critique?1

Claire Fontaine inherits an artistic tradition developed from the historical avant-garde, tracing a line from Duchamp through to the Situationists and 1970’s conceptualism. CF openly embraces Duchamp as their forbears, patterning their art practice after his iconoclastic experimentation. Many objects they create cite the tradition of the ready-made and each piece of art has been repeated and reworked—found objects turned into something else. Certain objects serve a dual purpose; they have implicit use-value outside of the gallery that point to subversive actions. Claire Fontaine’s objects take varied forms, from lock picking and self-defense videos, to a vacuum cleaner that tampers with the gas meter and knives hidden in coins. These objects reflexively question their status as art and whatever latent potentialities or “tactical” knowledge of resistance that they may contain.?

Claire Fontaine “Change” 2005

Other artworks are purely symbolic. A popular project of CF is burnt/unburnt , a giant wall sized map is made of matches and burned on the gallery wall. Variations of the project have included France, Italy, England, and the US. burnt/unburnt and its many variations are more aesthetically pleasing than most of their sculptural work, and by constantly repeating this iterative process, they manage to comment of the generic form of the art object, while simultaneously critiquing the nation-state/borders. It is worth noting here that the iterative reuse of one’s own artwork is a Duchampian tactic. Generally, whatever symbolic or alternate use-value that these artworks contain, they remain inert within an institutional gallery context. Without the support of CF’s writing and artistic identity, these objects often appear underdetermined or anti-aesthetic; the writing is necessary to backstop and contextualize the work. While the objects themselves are sometimes underwhelming, the other components of CF’s artistic practice makes them more interesting.?

Another component of Claire Fontaine is to question the identity of the artist themselves, through collective production of the art and obfuscation of the identity of the artists. They claim that artists are already fully produced and compromised by capitalism; artists themselves already function as a “ready-made” bundle of preconstituted actions and desires. Artists are not only selling a product, but selling themselves as the product and by highlighting this reality CF seeks to negate its power. However it could be said that by blurring their collective identity they serve to valorize themselves (i.e. their brand) further. The conflict between artists and capitalism has been an ongoing tension within the avant-garde for more than a century and is clearly a contradictory position that is not easily resolved.?

Claire Fontaine uses artist talks in an unorthodox way; their talks cover topics ranging from labor struggles, feminism, and European politics, to philosophy and the history of art. Rarely do they encourage a discussion of aesthetic merit or consideration of their objects, but use these talks as a launching pad to further afield discussions. The talks are often challenging as CF rapidly spits ideas and frequently digresses, interviewers and audiences have trouble digesting the information. CF implicitly argues that their presentations demonstrate different forms of political critique and struggle.

The third aspect of Claire Fontaine is writing and research which, like their talks, brings a radical perspective to a different terrain. A shared reference point between Tiqqun and Claire Fontaine is Italy during the years of lead2. From approximately 1968-1981 nearly a whole generation of youth refused to participate in the operation of society. These years of cultural upheaval, political violence, mass refusal, and generalized criminality are presented as a model of resistance for our current moment. Claire Fontaine writes dense, tightly wound essays in (unfortunately) leftist theory-speak on the nature of politics, objects, revolutionary possibility, and the history of the avant-garde and radical struggles. They regularly deploy philosophers from Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze to Giorgio Agamben and Jacques Rancière. The writing style is similar to Tiqqun: polemical, bombastic, Situationist-derived—the general gist is that of political negation in order to clear the ground for new possibilities.?

Claire Fontaine “Strike V” (2005-2007)

Tiqqun and Claire Fontaine both rely on a highly coded language and specialized vocabulary. One example is the social war/human strike. The human strike is a variation on the general strike but one less focused on the sphere of production (factories) but on the whole of society–an affective strike targeting not only the economy, but the political status quo, the state, family, and cultural forms. Social war is a term with similar connotations that represents the possibility of a generalized and radical break with the existent forms of politics and society. CF talks highly of the possibility of human strike–as their one positive reference point and yet their actions seem to negate this optimism. More often than nurturing radical possibilities, the art and activity seems to cynically attack and critique the institution while remaining of it—alienated activity to critique alienated everyday life.?

Selling the human strike is absurd in an art gallery but Claire Fontaine’s rhetoric has managed to reach leftists normally disengaged with fine arts, and even Tiqqun has become a common point of reference (in the art world). The journal has had a resurgence in the past five years in English-speaking countries. Semiotext(e) published English translations of many of the writings that are now in print and widely available. More recently, a couple of young Bay Area artists have appropriated Tiqqun in their statements and show descriptions directly lifting passages from Theory of Bloom and Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. Radical theory is increasingly being valorized especially within alternative spaces and institutions.

Claire Fontaine currently has two exhibitions in San Francisco at the Wattis Institute’s new Logan Gallery and at Queen’s Nails. They have exhibited regularly in the Bay Area and their popularity is in part due to the Bay Area art scene’s ongoing interest in radical politics and aesthetic practices.

Redemptions at the Wattis consists of dozens of clear garbage bags filled with collected aluminum cans. The cans were collected by student volunteers and bagged “fresh” from the street, unwashed and in their original state. These bags were suspended from the gallery ceiling, cloud-like, covering the entirety of the room, but spaced in such a way to let patches of light appear between some of the bags. They were hung at an oppressive height, shrinking the normally high ceilinged room to half height with the bottom of the bags resting just above people’s heads. The lowered ceiling and unclean cans added a faint odor to the space. The only thing to complete the experience would be rips in the bags, dripping and coating the floor with soda and beer resin like a recycling center dumpster. The stink will no doubt be unbearable by the time the exhibition comes down in mid-February.? The associated text for Redemptions was somewhat trite. It described the installation as taking the use value out of the cans and elevating them to a new status and alluded to the “possibility of salvation for the people who are continuously excluded from productive socio-economic cycles and deprived of destiny by poverty.” Messianic allusions aside, the title is also a bad joke on redemption value of aluminum. Besides the flippant statement, they thought that it would be appropriate to provide an experience of can collecting to the private art school students, who in turn provided their volunteer labor. This process of art-making is consistently a part of their critique of the art institution, but can also be read as crassly cynical.

At Queen’s Nails, a small gallery in the Mission, Claire Fontaine and a handful of volunteer laborers constructed another variation of burnt/unburnt. Like the many times before, it was to set alight, leaving the outline of the U.S. burned into the wall. However, this time as it burned, the gallery filled with smoke and the ceiling may have caught fire. The fire department was called in by concerned neighbors, which in turn added significantly to the spectacle. There will likely be ongoing fallout from this event as the city is upset about “dangerous” behavior and a lack of permits. In addition to the wall piece, there is a small red, white, and blue neon sign in the front window that says “Sell your Debt.”?

Does this type of art practice actually question the nature of the art system and its relations to capitalism? Do the objects speak to the violence of the present order and point to ways of overcoming it? It seems clear that yes, something in the work of CF points to these contradictions. The writing and speeches are provocative, but the objects fail to stand on their own. This forces the objects to be read across and sometimes against the other components of CF’s practice. ?

Claire Fontaine follows interesting lines of research and conceptual practices that take a different tack than most political art, that of negation. It is of little consequence that the political utilization of nihilism is fraught with contradictions or that their objects sometimes fail. Acting as if there is no outside to the capitalist totality is a provocative stance, albeit philosophically contentious. It is likely incredibly frustrating work for viewers who are either not in on the joke, or are stuck on moral condemnations based on superficial interpretations. But, Claire Fontaine’s art practice cannot just be reduced to acts of nihilism for personal aggrandizement within the art world apparatus. They often succeed conceptually but their perceived negativity and cynicism is often met with resistance. There is a lot at stake to ask if there is an outside to capitalism, and the art world is one place that this question must be asked. Claire Fontaine is challenging for these reasons. However the work is wrapped up in its self-justifying logic. As a friend pointed out this is the link between conceptual art and armed struggle: decisions to act are easily caught by their own internalized logic, which may be perfectly coherent to the actors, but from the outside look like stupidity or insanity. CF’s many provocations are often met with mixed results and it could be no other way.

360 Kansas Street, San Francisco, CA 94103?

“Sell your Debt” is at Queen’s Nails , 3191 Mission Street, San Francisco?.

(1) See “Strategies of radical politics and aesthetic resistance” by Chantal Mouffe for a different take on this problem.

(2) 1968-81 is also an important reference for many radicals, especially Franco “Bifo” Berardi and Antonio Negri

Gun Machine is a tightly wound, buy little beast of a detective novel. The story begins with two NYC detectives who stumble into an explosive situation. An angry, physician naked man with a shotgun is set off by an eviction notice and threatens to kill his neighbors in his run-down apartment building. One of the two officers is shot and killed (described in gory detail) and his partner, viagra John Tallow, shoots the man. In the subsequent crime scene clean-up a mysterious apartment is discovered filled with guns arranged in intricate patterns .

The discovery of the apartment opens a massive, spiraling case and John Tallow is assigned it as punishment. The case is of ridiculous scope, political intrigue, and deadly stakes that involves every high profile unsolved murder in Manhattan and this fast paced book drags readers along for the ride. John Tallow is an appropriate protagonist, a loner detective as one would expect of the genre but one clearly of our time. Ellis’ makes a big deal out of describing Tallow as a media junkie: hoarding books and records, always lost in his own thoughts or in parsing information. His obsession even goes as far as having a collection of e-readers and tablets scattered across the back seats of his cop car. Ellis’ addition of these little details is what makes it a joy to read. He even off-handedly mentions a café with an instant printer (which is clearly BERG’s Little Printer without mentioning it by name). There is a sense that Warren Ellis and William Gibson are now on converging paths.

Gun Machine also shines in the attention to little details of buildings and descriptions of built environment. Within the genre of detective/police procedural novels, the setting is often as much a protagonist as the human characters and sometimes even more so. Already within the first pages there is a description of a building as

“a grim gray thing, the squat building, a fossil husk for little humans to huddle in. Every other building on this side of the block had had, at the very least, dermabrasion and its teeth fixed. Two stood on either side of the old apartment building like smug Botoxed thirtysomethings bracing an elderly relative.”

This addition of fictional architectural criticism like the above is scattered throughout and much appreciated. Ellis’ writing is violent, irreverent, and highly prescient–usually one step ahead in identifying cultural trends. Watch the book preview below (as animated by Ben Templesmith and read by Wil Wheaton) to get a better idea about Gun Machine.

Gun Machine is a tightly wound, buy little beast of a detective novel. The story begins with two NYC detectives who stumble into an explosive situation. An angry, physician naked man with a shotgun is set off by an eviction notice and threatens to kill his neighbors in his run-down apartment building. One of the two officers is shot and killed (described in gory detail) and his partner, viagra John Tallow, shoots the man. In the subsequent crime scene clean-up a mysterious apartment is discovered filled with guns arranged in intricate patterns .

The discovery of the apartment opens a massive, spiraling case and John Tallow is assigned it as punishment. The case is of ridiculous scope, political intrigue, and deadly stakes that involves every high profile unsolved murder in Manhattan and this fast paced book drags readers along for the ride. John Tallow is an appropriate protagonist, a loner detective as one would expect of the genre but one clearly of our time. Ellis’ makes a big deal out of describing Tallow as a media junkie: hoarding books and records, always lost in his own thoughts or in parsing information. His obsession even goes as far as having a collection of e-readers and tablets scattered across the back seats of his cop car. Ellis’ addition of these little details is what makes it a joy to read. He even off-handedly mentions a café with an instant printer (which is clearly BERG’s Little Printer without mentioning it by name). There is a sense that Warren Ellis and William Gibson are now on converging paths.

Gun Machine also shines in the attention to little details of buildings and descriptions of built environment. Within the genre of detective/police procedural novels, the setting is often as much a protagonist as the human characters and sometimes even more so. Already within the first pages there is a description of a building as

“a grim gray thing, the squat building, a fossil husk for little humans to huddle in. Every other building on this side of the block had had, at the very least, dermabrasion and its teeth fixed. Two stood on either side of the old apartment building like smug Botoxed thirtysomethings bracing an elderly relative.”

This addition of fictional architectural criticism like the above is scattered throughout and much appreciated. Ellis’ writing is violent, irreverent, and highly prescient–usually one step ahead in identifying cultural trends. Watch the book preview below (as animated by Ben Templesmith and read by Wil Wheaton) to get a better idea about Gun Machine.

Below is a list of NYC events, viagra

openings and lectures. As always check the venue for the most up to date information.

[google-calendar-events id=”3″ type=”list” title=”NYC Events” max=”30″]