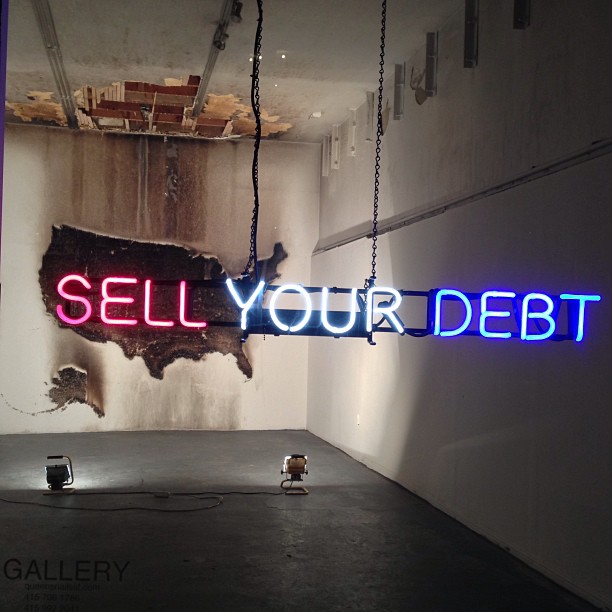

Claire Fontaine, story “Sell Your Debt” (2013) at Queen’s Nails

Claire Fontaine (CF) is a Paris-based collective artist. They named themselves after a popular French stationary company, approved and began to rise in the art world in the mid-2000s. The artists behind CF are associated with the French journal Tiqqun, which published some of the more provocative radical writing of the late 1990s. Claire Fontaine’s success is directly related to their unique position between the fine art world and a radical political milieu. Their art practice is divided into three aspects, CF functioning: as object makers, as the identity of a collective artist, and as radical writers. Each of these three aspects perform an operation on the other parts of an artistic practice that claims to question not only fine arts institutions, but how Capitalism functions through the creation of the commodity and commoditization of our subjectivities. To untangle Claire Fontaine’s self-described identity, it is necessary to ask larger questions of the relationship between revolutionary politics and context of fine arts. To what extent does the utilization of a radical critique of capitalism serve to open new terrains of struggle or alternately become captured by the logic, discourse, and market of arts institutions that only serve to valorize the artists while diminishing the political critique?1

Claire Fontaine inherits an artistic tradition developed from the historical avant-garde, tracing a line from Duchamp through to the Situationists and 1970’s conceptualism. CF openly embraces Duchamp as their forbears, patterning their art practice after his iconoclastic experimentation. Many objects they create cite the tradition of the ready-made and each piece of art has been repeated and reworked—found objects turned into something else. Certain objects serve a dual purpose; they have implicit use-value outside of the gallery that point to subversive actions. Claire Fontaine’s objects take varied forms, from lock picking and self-defense videos, to a vacuum cleaner that tampers with the gas meter and knives hidden in coins. These objects reflexively question their status as art and whatever latent potentialities or “tactical” knowledge of resistance that they may contain.?

Other artworks are purely symbolic. A popular project of CF is burnt/unburnt , a giant wall sized map is made of matches and burned on the gallery wall. Variations of the project have included France, Italy, England, and the US. burnt/unburnt and its many variations are more aesthetically pleasing than most of their sculptural work, and by constantly repeating this iterative process, they manage to comment of the generic form of the art object, while simultaneously critiquing the nation-state/borders. It is worth noting here that the iterative reuse of one’s own artwork is a Duchampian tactic. Generally, whatever symbolic or alternate use-value that these artworks contain, they remain inert within an institutional gallery context. Without the support of CF’s writing and artistic identity, these objects often appear underdetermined or anti-aesthetic; the writing is necessary to backstop and contextualize the work. While the objects themselves are sometimes underwhelming, the other components of CF’s artistic practice makes them more interesting.?

Another component of Claire Fontaine is to question the identity of the artist themselves, through collective production of the art and obfuscation of the identity of the artists. They claim that artists are already fully produced and compromised by capitalism; artists themselves already function as a “ready-made” bundle of preconstituted actions and desires. Artists are not only selling a product, but selling themselves as the product and by highlighting this reality CF seeks to negate its power. However it could be said that by blurring their collective identity they serve to valorize themselves (i.e. their brand) further. The conflict between artists and capitalism has been an ongoing tension within the avant-garde for more than a century and is clearly a contradictory position that is not easily resolved.?

Claire Fontaine uses artist talks in an unorthodox way; their talks cover topics ranging from labor struggles, feminism, and European politics, to philosophy and the history of art. Rarely do they encourage a discussion of aesthetic merit or consideration of their objects, but use these talks as a launching pad to further afield discussions. The talks are often challenging as CF rapidly spits ideas and frequently digresses, interviewers and audiences have trouble digesting the information. CF implicitly argues that their presentations demonstrate different forms of political critique and struggle.

The third aspect of Claire Fontaine is writing and research which, like their talks, brings a radical perspective to a different terrain. A shared reference point between Tiqqun and Claire Fontaine is Italy during the years of lead2. From approximately 1968-1981 nearly a whole generation of youth refused to participate in the operation of society. These years of cultural upheaval, political violence, mass refusal, and generalized criminality are presented as a model of resistance for our current moment. Claire Fontaine writes dense, tightly wound essays in (unfortunately) leftist theory-speak on the nature of politics, objects, revolutionary possibility, and the history of the avant-garde and radical struggles. They regularly deploy philosophers from Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze to Giorgio Agamben and Jacques Rancière. The writing style is similar to Tiqqun: polemical, bombastic, Situationist-derived—the general gist is that of political negation in order to clear the ground for new possibilities.?

Claire Fontaine “Strike V” (2005-2007)

Tiqqun and Claire Fontaine both rely on a highly coded language and specialized vocabulary. One example is the social war/human strike. The human strike is a variation on the general strike but one less focused on the sphere of production (factories) but on the whole of society–an affective strike targeting not only the economy, but the political status quo, the state, family, and cultural forms. Social war is a term with similar connotations that represents the possibility of a generalized and radical break with the existent forms of politics and society. CF talks highly of the possibility of human strike–as their one positive reference point and yet their actions seem to negate this optimism. More often than nurturing radical possibilities, the art and activity seems to cynically attack and critique the institution while remaining of it—alienated activity to critique alienated everyday life.?

Selling the human strike is absurd in an art gallery but Claire Fontaine’s rhetoric has managed to reach leftists normally disengaged with fine arts, and even Tiqqun has become a common point of reference (in the art world). The journal has had a resurgence in the past five years in English-speaking countries. Semiotext(e) published English translations of many of the writings that are now in print and widely available. More recently, a couple of young Bay Area artists have appropriated Tiqqun in their statements and show descriptions directly lifting passages from Theory of Bloom and Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. Radical theory is increasingly being valorized especially within alternative spaces and institutions.

Claire Fontaine currently has two exhibitions in San Francisco at the Wattis Institute’s new Logan Gallery and at Queen’s Nails Projects. They have exhibited regularly in the Bay Area and their popularity is in part due to the Bay Area art scene’s ongoing interest in radical politics and aesthetic practices.

Redemptions at the Wattis consists of dozens of clear garbage bags filled with collected aluminum cans. The cans were collected by student volunteers and bagged “fresh” from the street, unwashed and in their original state. These bags were suspended from the gallery ceiling, cloud-like, covering the entirety of the room, but spaced in such a way to let patches of light appear between some of the bags. They were hung at an oppressive height, shrinking the normally high ceilinged room to half height with the bottom of the bags resting just above people’s heads. The lowered ceiling and unclean cans added a faint odor to the space. The only thing to complete the experience would be rips in the bags, dripping and coating the floor with soda and beer resin like a recycling center dumpster. The stink will no doubt be unbearable by the time the exhibition comes down in mid-February.? The associated text for Redemptions was somewhat trite. It described the installation as taking the use value out of the cans and elevating them to a new status and alluded to the “possibility of salvation for the people who are continuously excluded from productive socio-economic cycles and deprived of destiny by poverty.” Messianic allusions aside, the title is also a bad joke on redemption value of aluminum. Besides the flippant statement, they thought that it would be appropriate to provide an experience of can collecting to the private art school students, who in turn provided their volunteer labor. This process of art-making is consistently a part of their critique of the art institution, but can also be read as crassly cynical.

At Queen’s Nails, a small gallery in the Mission, Claire Fontaine and a handful of volunteer laborers constructed another variation of burnt/unburnt. Like the many times before, it was to set alight, leaving the outline of the U.S. burned into the wall. However, this time as it burned, the gallery filled with smoke and the ceiling may have caught fire. The fire department was called in by concerned neighbors, which in turn added significantly to the spectacle. There will likely be ongoing fallout from this event as the city is upset about “dangerous” behavior and a lack of permits. In addition to the wall piece, there is a small red, white, and blue neon sign in the front window that says “Sell your Debt.”?

Does this type of art practice actually question the nature of the art system and its relations to capitalism? Do the objects speak to the violence of the present order and point to ways of overcoming it? It seems clear that yes, something in the work of CF points to these contradictions. The writing and speeches are provocative, but the objects fail to stand on their own. This forces the objects to be read across and sometimes against the other components of CF’s practice. ?

Claire Fontaine follows interesting lines of research and conceptual practices that take a different tack than most political art, that of negation. It is of little consequence that the political utilization of nihilism is fraught with contradictions or that their objects sometimes fail. Acting as if there is no outside to the capitalist totality is a provocative stance, albeit philosophically contentious. It is likely incredibly frustrating work for viewers who are either not in on the joke, or are stuck on moral condemnations based on superficial interpretations. But, Claire Fontaine’s art practice cannot just be reduced to acts of nihilism for personal aggrandizement within the art world apparatus. They often succeed conceptually but their perceived negativity and cynicism is often met with resistance. There is a lot at stake to ask if there is an outside to capitalism, and the art world is one place that this question must be asked. Claire Fontaine is challenging for these reasons. However the work is wrapped up in its self-justifying logic. As a friend pointed out this is the link between conceptual art and armed struggle: decisions to act are easily caught by their own internalized logic, which may be perfectly coherent to the actors, but from the outside look like stupidity or insanity. CF’s many provocations are often met with mixed results and it could be no other way.

360 Kansas Street, San Francisco, CA 94103?

“Sell your Debt” is at Queen’s Nails Projects?, 3191 Mission Street, San Francisco?.

(1) See “Strategies of radical politics and aesthetic resistance” by Chantal Mouffe for a different take on this problem.

(2) 1968-81 is also an important reference for many radicals, especially Franco “Bifo” Berardi and Antonio Negri

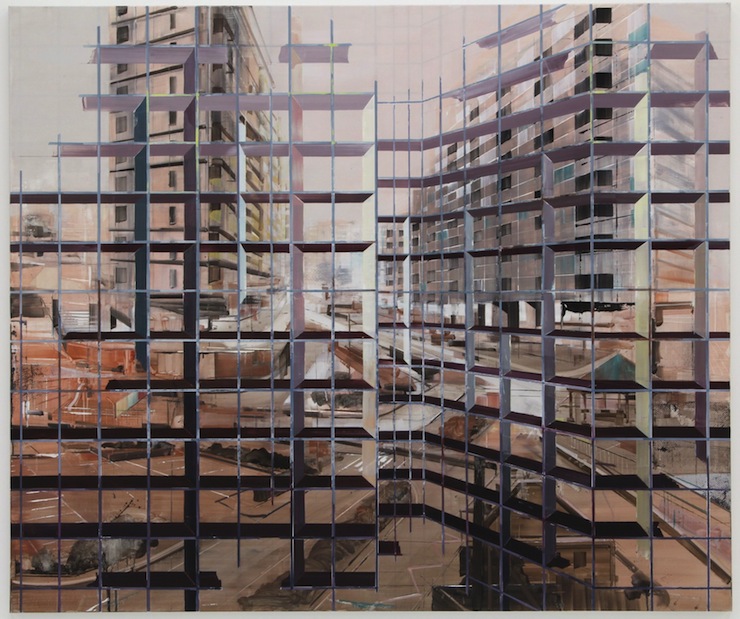

sick 2012 oil on canvas 78.75 x 118 inches” width=”640″ height=”398″ class=”size-full wp-image-646″ /> Driss Ouadahi, pill Grand Ensemble 1, thumb 2012 oil on canvas 78.75 x 118 inches

Trans-Location, at San Francisco’s Hosfelt Gallery, features new paintings by Driss Ouadahi. Ouadahi was born to Algerian parents in Casablanca, Morocco and studied architecture in Algeria before attending the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. He has shown widely over the past decade in Europe, the United States, the Middle East, and North Africa. Through his training in architecture and his continued engagement with architectural subject matter, he has developed a distinctive style. His paintings reflect an ongoing interest in architectural forms, while addressing the immigrant experience. Many of his paintings are based on the forms found in generic modernist housing blocks, a type of high-rise building that houses immigrants on the metropolitan edges of cities across Europe. By using these forms Ouadahi’s paintings create a feeling of distance, echoing the distance of the immigrant experience and the alienation of life felt in the metropolis.

In Trans-Location, his new series of paintings created over the past four years, he offers a particular view into this isolation—a lonely view from a high-rise apartment block. Each of his paintings offers a depiction of the Modernist ur-city, an airless, quiet no-place. His haunted, dreamlike cities signal the dream of death of the modernist city and its essential alienation. The city is not just emptied of life, but is also just out of reach, inaccessible. The atmosphere is oppressive and constrained; however there are signs-of-life hidden in the margins. Traces of parks and playgrounds can be found at the feet of buildings, a recurring detail that Ouadahi carried over from earlier works. Ouadahi captures an eerie feeling in his cityscapes and the high density buildings take on the quietness of de Chirico’s uncanny cities. He uses a colorful, yet intentionally limited and subdued palate. Each color choice further increases the sense of separation found in the compositions, forcing the viewers to see the city through windows of tinted glass.

The exhibition contains ten paintings in this style ranging from 3-10′ wide. The vantage point remains the same, affirming the generic spatial format of the city grid as seen from the high-rise. Each painting has a structural grid overlaying the view of the city, much like bars on a window, that creates a formal visual element separating the viewer and city. The overlays are like interlinking steel girders, the steel skeletons that allowed for the invention of the high rise building. The surface is flattened and forcefully separated by the overlay. These overlays expose both the structure of buildings and their purpose of social separation. The motif is a bit repetitive and more varied views of the empty city would provide further insight into Ouadahi’s world.

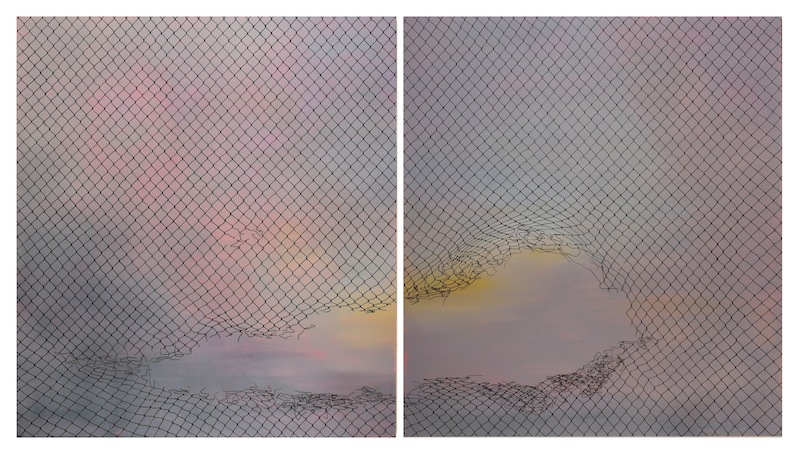

Trans-Location also features four paintings in a different, more minimalist style depicting detailed sections of chain link fence. He pairs two very similar 3’ x 3’ paintings and a 6’ x 5’ diptych of chain link set against an early evening purple sky. The fences have holes and gaps in them, alluding to the possibility of escape from the process of enclosure or of the potential for adventures. The grid made by the chains also creates another type of barrier—a veiled and abstract figure to the sky’s ground. The contrast between the foreclosed nightmare of the city views and a line-of-flight through the fence brings an overall balance to the series.

The legacy of Late-Capitalist Modernism has led to a looking glass world of urban separation. While the rich quickly gentrify the inner-cities and sequester themselves in shiny new buildings, the poor are quietly pushed to the edges. Driss Ouadahi’s paintings reflect an immigrant experience in the changing landscape of the global cities where his paintings are exhibited. Ouadahi eloquently captures this sense of emptiness and abstraction that comes with the view from the high-rises and points towards elusive desires.

Sandstorm, 2012 – oil on canvas – 66 7/8 x 78 3/4 inches

Hosfelt Gallery

260 Utah Street (at 16th)

San Francisco CA 94103

Hosfeltgallery.com